“We hold these truths to be self-evident…all men are created equal....” These words, instituted by the Founding Fathers and reinforced by President Lincoln, are the foundation of the nation. However, these ideals were still met with with reality, and the strength of their resolve was tested before the Declaration of Independence was even signed. They were challenged again during the the American Civil War, and Lincoln wonders “whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure”. Though the fighting ended in spring of 1865, for some the war raged on long after, and the words would be tested time and again, including during one of the most pivotal court cases regarding racial equality.

Jim Crow: the song that be came a scapegoat

In the aftermath of Reconstruction, which ended in 1877, many Southern states reverted to their antebellum ways of white supremacy. The new State legislatures enacted so-called Jim Crow laws to legally segregate the races, effectively imposing second-class citizenship upon African Americans. ("Jim Crow" was the title of a minstrel show song that sterotyped them.) These laws created separate schools, parks, waiting rooms, etc. for blacks and whites, and the separations were enforced with the threat of criminal penalty. In its ruling in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the Supreme Court made clear that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment provided no guarantee against segregation within private holdings. It would now be asked to rule on what protection the 14th Amendment offered in matters of public segregation.

For some time, activists had looked for a person who could help to rid America of discriminatory laws against blacks once and for all. Homer Plessy, who strongly disagreed with these “Jim Crow” laws, was born a free man, but was described as an octoroon, or hereditarily ⅛ black. His heritage was not present in his skin tone; however, due to the South’s prevailing “one drop rule”, Plessy was considered a black man. (Regardless of how removed a person may be from a black ancestor, if there is a black person in his direct lineage, “Black” was the legal ethnicity.) In June of 1892, Plessy agreed to travel from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana on the East Louisiana Railroad. At the time, African-Americans traveling in Louisiana were required to sit in a blacks-only railroad car. Plessy refused, and took a seat in the “whites only” car. When told to move, he refused, was arrested, and taken to the New Orleans jail.

Plessy’s conviction was sustained through the state courts, and the case ultimately found its way to the United States Supreme Court. Plessy argued the “separate but equal” statute violated both the Thirteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment. He contended that the reputation of being white was a form of “property” and that the state, by declaring Homer Plessy non-white, denied his property rights and implied the inferiority of the Negro Race. However, the majority of the Court rejected this view. Instead, it contended that the law separated the two races as a matter of public policy. Justice Brown wrote,

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

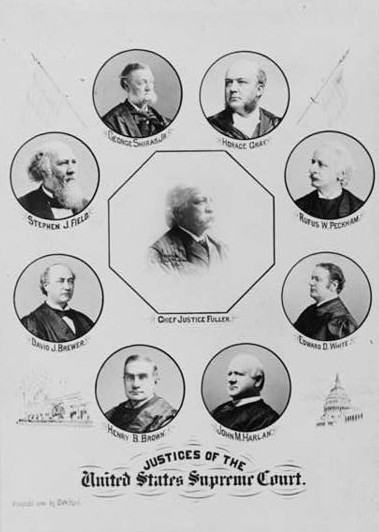

In a 7-1 decision (one judge abstained), the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Ferguson, rejecting Plessy’s Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendment arguments and instead putting its stamp of approval on the doctrine of “separate but equal.” But is “separate but equal” what the Founding Fathers or Abraham Lincoln meant by “All men are created equal”?

Truth: Self-evident or Subjective?

Original drafts of the Declaration of Independence forbade slavery in the new United States. However, in order to ratify the Declaration, a unanimous vote was required. Southern states refused to vote for ratification unless references to slavery were removed; if the document was ratified as it was written, then the slaves would be free and equal to whites, triggering a significant economic repercussion. Abolitionists such as John Adams were faced with a hard choice: lose the battle over slavery, or the war against King George’s tyranny. Believing that suffering under British rule was the greater ill, and that ending slavery would be something the new nation could agree on once it was independent, they agreed to the compromise. They never conceived that American innovation - especially Eli Whitney’s cotton gin - would cause slavery to skyrocket and lead to a “great Civil War.”

During the Civil War, President Lincoln attempted to make peace between pro- and anti-slavery activists, just as the founders did “Four score and seven years...” prior. Initially, Lincoln tried to resolve things peacefully, giving the people the decision to be a slave country or a free one, but reminding them that they have to accept the consequences resulting from their choice. When the people still could not come to a decision and war followed, Lincoln used his executive powers as the tiebreaker, issuing the admittedly imperfect Emancipation Proclamation. He follows in the footsteps of the founders, reminding the people gathered at Gettysburg that they were a nation “...conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” However, when Lincoln says “...all men are created equal”, he truly means all people, regardless of race or ethnicity, being one and the same, not segregated by skin tone. Looking back at the Andrew Johnson administration (effectively the whole of Lincoln’s second elected term) and outright and obstinate Congressional opposition to a grudge-less reunification, it is difficult not to wonder how the nation would have rebuilt itself had Lincoln not become the victim of an assassin’s bullet.

Was the equality for Americans that John Adams argued for and Abraham Lincoln memorialized the fallen at Gettysburg over merely a dream? In one of the most shameful decisions ever issued by the United States Supreme Court, Homer Plessy lost his bid to be considered neither white nor black but simply American. In a nation where a simple majority was enough for an law to pass, the fact that Homer was “7/8ths white” (notably a larger percentage than the 7/9ths vote that demanded he sit in the black car) did not matter. As time went on, southern states continued to blame blacks for the fallout of the Civil War and found ways to continue to treat them as less than equal. “Jim Crow” laws littered the south, and eventually even the words “separate but equal” would begin to be interpreted subjectively. Is it any wonder that decades later, a small, quiet woman from Alabama would also say, “I’m tired of giving in,” and refuse to move from her seat on the bus?

©2012- 2015 Adventures with Jude. All rights reserved. All text, photographs, artwork, and other content may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written consent of the author. http://adventureswithjude.com

No comments:

Post a Comment