“Mass production” is the name given to the method of producing goods in large quantities at low cost per unit. Two American innovators stand out in history as revolutionizers of mass production. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin transformed the American south into a worldwide export leader while his and weapons featuring interchangeable parts laid the framework for modern arms production. Henry Ford assembly-line modes of production irrevocably altered manufacturing and availability of goods. Though their paths never crossed, these two men revolutionized American manufacturing.

The Father of American Technology

Eli Whitney was born on December 8, 1765, in Westboro, Massachusetts. He grew up on a farm where mechanic devices were rudimentary, igniting an affinity for machine work and technology. As a youth during the Revolutionary War, he became an expert at making nails from a device of his own invention. As America settled into it’s independence in 1789, Whitney entered Yale College, graduating in 1792 with aspirations of becoming lawyer. The newly degreed Whitney was hired to be a tutor in South Carolina. Catherine Greene, the widow of Revolutionary War hero Nathaniel Greene, was also sailing on the boat taking him to his new employment. Greene offered Whitney a position reading law at her Mulberry Grove, Georgia plantation. When Whitney found out that his agreed-upon tutoring salary was to be halved, he refused the job and instead accepted Green’s offer. There he met Phineas Miller, another Yale alum, who was Greene’s fiancé and manager of her estate.

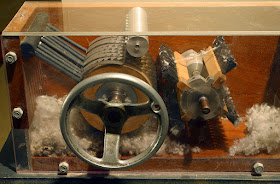

|

| Cotton Gin Tom Murphy VII/US Public Domain |

_-_hi_res.jpg) |

| Cotton Gin Patent US Public Domain |

While it is true that the cotton gin was originally Whitney’s idea, he is not fully responsible for the growth of slavery. Despite being patented, farmers widely pirated the device to cut costs. Whitney spent years in expensive legal battles, and by the turn of the century he agreed to license gins at an affordable rate. Southern planters were ultimately able to reap huge financial windfalls from the invention while Whitney made almost no net profit, even after he was able to receive monetary legal settlements from various states. During his difficulties in receiving compensation for the cotton gin, Whitney’s next big venture would involve the production of arms and champion the interchangeable-parts system.

With a potential war with France on the horizon, the American government looked to private contractors to supply firearms. Whitney promised to manufacture 10,000 rifles within a two-year period of time, and the government accepted his bid in 1798. At the time, muskets were generally assembled in their entirety by individual craftsmen, with each weapon having its own distinct design. Returning to New England to start his business, Whitney devised milling machines that would allow laborers to slice metal by a pattern and produce one particular, specific part of a weapon. When put together, each part, though made separately, became a working model. Making the shift from general gunsmithing to specialized parts manufacturing was challenging; it took 10 years for him to complete the manufacture of 10,000 muskets. Yet even with the delay, the government didn’t give up. Whitney soon received another order for 15,000 guns, which he was able to supply in just two years. While there is record of other inventors having come up with the idea of interchangeable parts, Whitney is credited with pushing Congress to support weapons production and helping to propagate a manufacturing system that has influenced modern assembly lines. His pursuits have often led him to be called the “Father of American Technology.” In 1817, Whitney wed Henrietta Edwards. The couple would have several children, with Eli Whitney Jr. continuing to work in his father’s manufacturing business as an adult. The elder Whitney died of prostate cancer on January 8, 1825, in New Haven, Connecticut, with a legacy of great invention but not great wealth.

A Car for Every Garage

|

| Model T Automobile |

|

| Ford's Assembly Line US Public Domain |

|

| The Dearborn Independent US Public Domain |

Two men, Eli Whitney and Henry Ford, revolutionized American manufacturing. Eli Whitney‘s cotton gin streamlined the process of extracting fiber from cotton seeds and inadvertently propelled slavery to new heights. When his patent for the device became widely pirated, Whitney pushed the “interchangeable parts” mode of product design. Henry Ford revolutionized the production of the automobile, making his assembly-line product affordable for even the men building it. While each man’s company eventually lost its’ market dominance, Eli Whitney and Henry Ford left a lasting impact on technological and product development.

Cover Image Credits:

Eli Whitney - Library of Congress/US Public Domain

Henry Ford - Library of Congress/US Public Domain

©2012- 2015 Adventures with Jude. All rights reserved. All text, photographs, artwork, and other content may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written consent of the author. http://adventureswithjude.com

No comments:

Post a Comment